By “tolerant of uncertainty” we mean that particular elements of a modular design may be changed after the fact and in unforeseen ways: see Design Rules, Volume 1 The Power of Modularity.

Techopedia defines modularity, from a software engineering perspective as referring

… to the extent to which a software/Web application may be divided into smaller modules. Software modularity indicates that the number of application modules are capable of serving a specified business domain.

To successfully implement Modularity, the internal implementation details of a Module must be shielded from the Module’s external environment. The external environment being the aggregate of all other modules, the underlying runtime and higher level Services. The only permissible interactions between the Module, and its host ‘Environment’, are then via the Module’s (in a software context) public Interfaces.

Once achieved, the internal mechanisms within a Module are decoupled from the external environment.

Regarding the importance of Modularity in Software, which of course includes Java Modularity, Parnas in his seminal paper On the Criteria to be Used in Decomposing Systems into Modules, states…

“The major advancement in the area of modular programming has been the development of coding techniques and assemblers which (1) allow one module to be written with little knowledge of the code in another module, and (2) allow modules to be reassembled and replaced without reassembly of the whole system. This facility is extremely valuable for the production of large pieces of code…”

He goes on to explain that…

“… the impact of change on a Modular composite system is dictated by how the system was decomposed. If a small change in a single Module causes a cascade of many downstream changes in other modules; then Modules in the system are tightly-coupled. However if the change results with minimal/no downstream changes, then the Modules in the System are loosely-coupled.”

Answer: Software Complexity

Agility, Adaptability and Low Maintenance are essential characteristics required by tomorrow’s software ecosystems (e.g., Smart City and Industry 4.0). However, as DARPA realize, today’s software systems are complex and fail to meet these objectives.

Modern-day software systems, even those that presumably function correctly, have a useful and effective shelf life orders of magnitude less than other engineering artifacts…

while an application’s lifetime typically cannot be predicted with any degree of accuracy, it is likely to be strongly inversely correlated with the rate and magnitude of change of the ecosystem in which it executes.

– Building Resource Adaptive Software Systems – The DARPA BRASS Initiative 2015

Realizing this, DARPA issued the challenge to create software systems that avoid obsolescence; to create software ecosystems that are able to run for more than 100 years. Such software ecosystems must be economically sustainable over these extended periods, and to achieve this longevity they must be cost-effective to adapt and evolve and be simple to maintain, or more probably, be self-maintaining.

While this DARPA initiative is recent, software scientists have been aware of these foundational issues since the early 1970’s. Notable insights into the nature of this problem include:

Gall’s Law (1975)

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be patched up to make it work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system.

Lehman’s Law (1974)

As a system evolves, its complexity increases unless work is done to maintain or reduce it.

Yet, a decade into ‘virtualization’ and more recently Containerisation and these maintainability and evolvability goals seem more elusive than ever.

Why is this so?

While ‘Structural Complexity’ and ‘Change’ are challenges shared by all engineering disciplines; it is perhaps the fluidity and rate of change that uniquely differentiates software engineering; perhaps aligning it closer to Biological or Social Systems.

And so, it is perhaps to those disciplines we should look to for guidance?

Biological, Ecological and Social systems are neither chaotic or completely deterministic in behavior; rather they are Agile and able to Adapt to the environments within which they find themselves embedded. Systems that achieve this while maintaining internal organizational patterns are collectively referred to as Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS).

All Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) are composed of a hierarchy of structural layers; each layer internally modular; thereby building an intricate hierarchy of boundaries and signals.

– Signals and Boundaries – John Holland

To accommodate structural change Systems must attempt to localize and/or minimize the effects of Change.

To achieve this, components within the System that are closely related

need to be colocated together ideally within the same logical unit; i.e., a Module.

Meanwhile, components that evolve at different rates, and/or could be used separately in different runtime contexts, should be in separate Modules, and these Modules should be Loosely Coupled via the published Interfaces that change much more slowly over time.

In software engineering these principles are referred to as the Principles of Package Cohesion which state that:

Hence to enable change, Modules must be loosely coupled to each other.

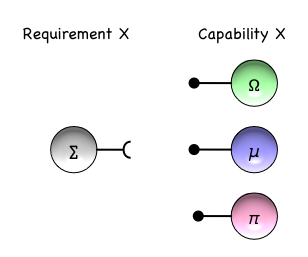

Loose coupling cannot be achieved if Modules refer to each other explicitly by unique names; e.g., in the following diagram Model ∑ explicitly references a dependency on the named Module Ω.

Rather, to enable substitution, Module relationships need to be expressed in terms of the Capabilities they expose to their Environment, and what they Require from their Environment. We see that Module ∑ Requires a Capability X, and that this Capability can be provided by any one of the Modules Ω,µ,π. Given the diverse set of implementations of Service X, substitution is possible, and so change is possible.

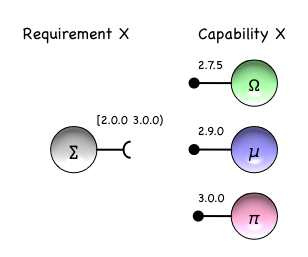

It is also useful to have some form of mechanism to communicate the impact of a change, and in the context of software engineering this is achieved by Semantic Versioning.

As shown, Module ∑ from its perspective now states a constraint on the usable versions of Service X. The constraint [2.0.0, 3.0.0) states that only Services at versions 2.0.0 or higher, but less than 3.0.0, will be considered; hence π is no longer a candidate but Ω,µ remain valid options.

The Principles of Package Cohesion, provide guidance concerning the inter-relationship between Loosely-Coupled Modules:

These rules attempt to minimize the impact of change upon the graph topology created by the inter-dependent set of Modules.

It is also worth considering the work of Zanetti and Schweitzer on using complex network theory to estimate the coherence between the modularity of the dependency network of large open source Java projects and their decomposition in terms of Java packages.

With respect to structural hierarchy Parnas states…

“The existence of the hierarchical structure assures us that we can “prune” off the upper levels of the tree and start a new tree on the old trunk. If we had designed a system in which the “low level” modules made some use of the “high level” modules, we would not have the hierarchy, we would find it much harder to remove portions of the system, and “level” would not have much meaning in the system.”

and

“We must conclude that hierarchical structure and “clean” decomposition are two desirable but independent properties of a system structure.”

Hence Parnas sees Hierarchy and Modularity as orthogonal concerns. However, this is not quite the case.

Something strange happens when we apply Modularity to a structure. Let’s take Java as an example;

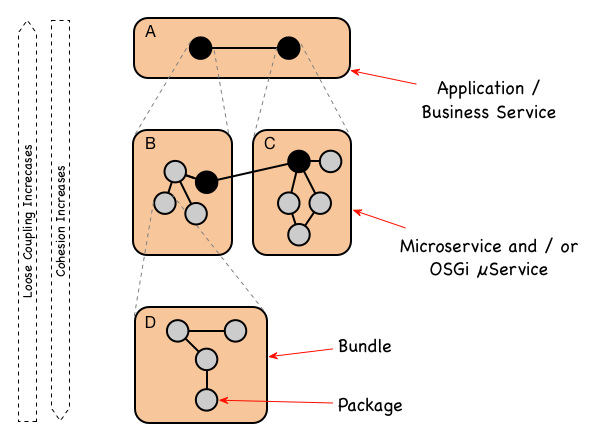

Classes – the finest level of Modularity.Classes we group them into abstractions we call Packages.Packages we group Packages into abstractions we call OSGi Bundles.The introduction of Modularity at one structural layer actually introduces a new higher layer of structural abstraction.

Modularity and the runtime structural Hierarchy are therefore actually closely related concepts.

If implemented correctly, as we climb up through this structural hierarchy cohesion should decrease and loose-coupling increase.

However, now for each new layer of this hierarchy, we must address the questions:

Hence, by creating new structural abstractions we’ve created new layers of complexity. Moreover, the Actors that need to deal with this complexity are unlikely to be the Developers that wrote the original code. Indeed, as is discussed in the next section on Measuring Complexity, this is actually undesirable.

This sounds like a lot of effort? So are we really reducing Complexity? How are we winning?

How can you measure complexity?

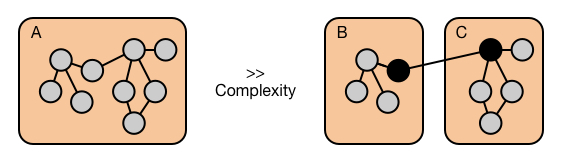

Intuitively one might expect software complexity to grow with respect to the number of links (i.e. links being lines of code calling a method or using a field) inside the code base. In the following diagram we see that module A has 9 internal links, hence a reasonable complexity measure might be proportional to 92. Meanwhile, for the Modular alternative, we see that the combined complexity estimate (Module B and C together) is 32 + 62, which is almost half.

Variations on the above approach have been investigated since the early 1970’s. For example, in 1977 Halstead proposed that software Complexity metrics should reflect the implementation or expression of algorithms, but be independent of their execution on a specific platform. Halstead’s approach mirrored Physics’ approach to the measurement of invariant properties of matter (like the volume, mass, and pressure of a gas) and the relationships between these properties (Boltzman Ideal Gas equation).

The problem with such studies is that an absolute complexity measure – however derived – is abstract and means nothing in isolation. Such measures are relative in nature and we need to be able to map relative changes in complexity through to measurable consequences.

Quantitaive Complexity measures provide a more direct route to cost/benefit analysis.

Qualitative measures of software complexity can be traced back to Scott Woodfield’s research in 1979 An Experiment on Unit Increase in Problem Complexity. With the participation of 48 experienced developers, Woodfield conducted a series of experiments to investigate how different types of modularization and comments relate to programmers’ ability to understand, correct and modify programs.

Woodfield’s research is summarised by Robert Glass in his book Facts and Fallacies of Software Engineering – sometimes referred to as Glass’s Law which states:

For every 25% increase in problem complexity (F), there is a 100 percent increase in complexity (C) of the software solution.

As demonstrated in the blog post The Equation every Enterprise Architect Should Memorize – Roger Sessions, this expression can be recast into:

A Module with b functions is 10log(C) x log(b) / log(F) times more complex than a Module that contains just 1 of the functions.

If we apply Glass’s complexity measure to the previous example we find the following:

Note: The exponent 3.11 in Glass’s law is derived via a qualitative process. Hence it is reasonable to adjust this value if data from your environment indicates that it should be higher or lower.

Armed with Glass’s Law we can now revisit the previous Complexity v.s. Hierarchy discussion.

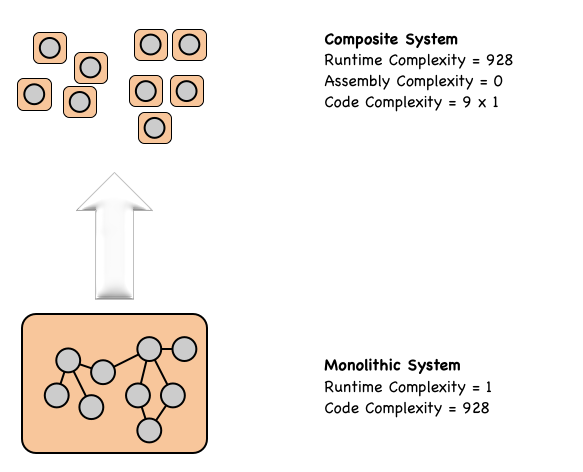

We will start by seeing what happens if we ignore any Cohesion concerns and break our pet Monolith into 9 isolated Modules; each Module representing one function. These functions are independently deployed into a traditional Production environment as 9 independent microservices.

This process results in a massive decrease in Developer complexity: i.e. 928 to 9 × 1. However, as the traditional runtime has no automatic assemble/orchestration capabilities, the runtime complexity exposed to Operations explodes from the single running monolith (Complexity 1) to having to configure a number of inter-related microservices (Complexity 93.11 = 928). Without appropriate runtime automation, this, therefore, becomes an Operational nightmare.

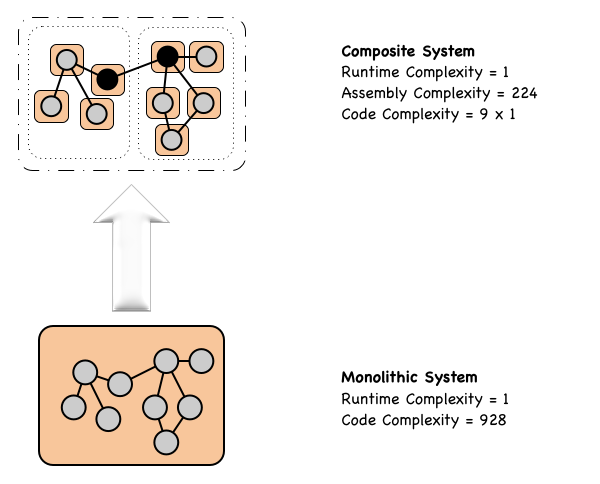

To realize the significant benefits created by Modularity, the release toolchain and runtime platform must be capable of automatically Orchestrating and Assembling the required runtime Composite System from the available Modules. This shields Operations from the structural details of the composite system and presents them with a single simple entity to manage.

Once achieved, we have now reached the point where:

By using release tooling and the runtime to automatically manage assembly and orchestration results in an environment that environment is orders of magnitude simpler and more flexible.

Two questions often arise:

Alenezi and Zarour in their paper “Modularity Measurement and Evolution in Object-Oriented Open-Source Projects” confirm that:

Enhancing our ability to understand and capture software evolution is essential for better software quality and easier software maintenance process. One of the software characteristics that helps in achieving this is software modularity.

This work identified that there are some successful approaches to measuring modularity, however the answer to ‘How modular should I be?’ really is …it depends… on the specifics of your project and which level of the structural hierarchy your are responsible for.

Software Complexity is a foundational problem and Modularity is the solution to that problem. However, Modularity is not a one time apply and forget activity. The Modularization process creates a structural hierarchy and introduces new management considerations for each new layer in that hierarchy.

However, even after accounting for the new layers of structural complexity created by Modularity, the reduction of overall System Complexity is profound.

Of course, the most important complexity measure, and the one of most interest to senior management is expressed in the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) of the System.